Written by Gunnar Epping

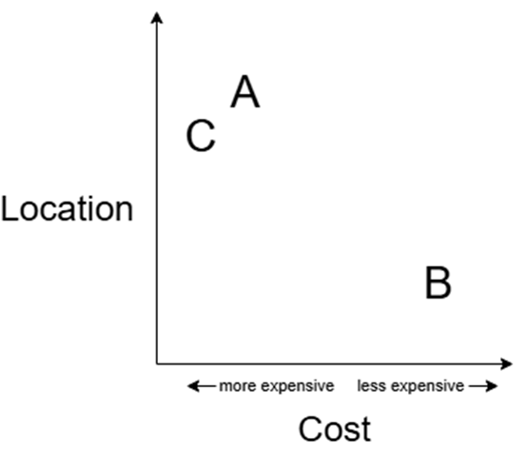

Suppose you are looking for a new apartment and deciding between option A, which is expensive but in a great location, and option B, which is cheap but in a bad location. Also assume that given how you weigh price and location, you do not favor one option over the other such that there’s a 50% chance you select option A and a 50% chance you select option B.

Now suppose, in addition to options A and B, you are also considering a third apartment, option C. Option C is slightly more expensive than option A and is in a slightly worse location than option A, but still a far better location than option B. The figure below illustrates the relative value of each option on the two attributes being considered.

Now that this third option has been introduced, how does this impact your decision-making process? Perhaps you may compare option A to option C and think to yourself, “Although both are more expensive than option B, option A is less expensive and in a better location compared to option C, so let’s go with that one.” This sort of thinking is an example of a context effect in decision-making. The context here is the set of options being considered. By changing the choice set from options A and B to options A, B, and C, option A looks like a better choice than option B. From a rational standpoint, introducing option C shouldn’t impact your indifference between options A and B because option C is irrelevant given that it is inferior to option A on both attributes. Nevertheless, decades of empirical research have reported evidence supporting the presence of context effects in decision-making (Huber et al., 1982).

Context effects are theorized to occur because of working memory constraints, attention, and the comparative process employed in decision-making. When only considering two options, you may be able to hold both options and their attributes in working memory when deciding between them. However, with the addition of more options, you may not be able to consider all options and attributes at once and instead attend to only a pair of options at one time. As a result, you make three comparisons when selecting your apartment (A versus B, A versus C, and B versus C) rather than simultaneously comparing A versus B versus C. When comparing A versus B, you are still indifferent between the two and don’t exhibit a preference for either option. When comparing A versus C, you develop a strong preference for option A since it is superior to option C on both attributes. When comparing B versus C, you develop a weak preference for option B. Aggregating your preference across the three comparisons, option A appears to be the best apartment.

Context effects that arise from changes to the choice set are not limited to consumer choice as they have also been found to impact perceptual decisions. For example, Trueblood et al. (2013) reported context effects when people evaluate the area of rectangles. The figure below depicts an example of a trial from this experiment, along with a plot depicting each rectangle’s relative height and width.

Although rectangles A and B both have the same area, people tended to judge rectangle A as having the greatest area among the three options.

Moreover, context effects are not limited to human behavior, as other animals have been shown to also exhibit context effects. For example, monkeys exhibit context effects using a similar perceptual task as described above (Parrish et al., 2013) and both honeybees and hummingbirds exhibit context effects in selecting flowers to forage from (Latty & Trueblood, 2020; Bateson et al., 2003). These studies support the idea that context effects are a universal property of choice behavior, regardless of setting or species.

People should be aware of context effects because it encourages us to reflect on the actual value or utility of different options, rather than being swayed by comparisons and irrelevant options. For example, businesses and marketers often exploit these effects to nudge people toward specific purchases. A company may offer 3 subscription plans that vary in terms of cost/month and number of months the subscription plan covers. They could attempt to manipulate you into purchasing a specific plan (call this plan A) by making one of the three plans inferior to plan A in terms of both cost per month and number of months. Therefore, developing an awareness of context effects helps people recognize when their preferences are being shaped, avoid being manipulated by marketing tactics, and make decisions that best align with their values and preferences. Want to test your knowledge of context effects in decision-making or provide feedback on the article? Please do so here.

References:

Bateson, M., Healy, S. D., & Hurly, T. A. (2003). Context–dependent foraging decisions in rufous hummingbirds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 270(1521), 1271-1276.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., & Puto, C. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: Violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. Journal of consumer research, 9(1), 90-98.

Latty, T., & Trueblood, J. S. (2020). How do insects choose flowers? A review of multi‐attribute flower choice and decoy effects in flower‐visiting insects. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89(12), 2750-2762.

Parrish, A. E., Evans, T. A., & Beran, M. J. (2015). Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) exhibit the decoy effect in a perceptual discrimination task. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 77, 1715-1725.Trueblood, J. S., Brown, S. D., Heathcote, A., & Busemeyer, J. R. (2013). Not just for consumers: Context effects are fundamental to decision making. Psychological science, 24(6), 901-908.