Sophia Priatka and Mackenzie Siesel joined the lab in Fall 2025 as new PhD students. Sophia completed her undergraduate degree at Purdue University. Mackenzie completed her undergraduate degree from The Ohio State University. Welcome to you both!

Congratulations Dr. Epping and Dr. Hasan!

Gunnar Epping and Eeshan Hasan both successfully defended their dissertations this summer. Gunnar will start full-time at Centaur Labs. Eeshan is joining The Ohio State University as a postdoc. Congratulations to you both!

Learn about Research in the Lab: Quantum Cognition: characterizing human behavior as quantum-like

Written by Gunnar Epping

What are the chances you’ve heard of “quantum cognition”? I assume that the chances are low, so let me outline quantum cognition, a useful and relatively recent approach to studying human judgment and decision-making. It might be surprising to see the word “quantum” outside of physics, yet quantum theory is nothing more than a probability theory. It is a set of rules that can be used to determine the likelihood of different events. While it may not always be obvious, we frequently utilize some theory of probability in our everyday lives.

For example, if we roll a pair of dice, we know the likelihood of rolling two 1’s is 1/36, but how do we arrive at this likelihood? First, we know that a die has 6 sides and therefore the likelihood of 1 landing up is 1/6. Second, we assume that the two dice are independent of one another. Based on classical probability theory (the probability theory we are most familiar with), the likelihood of the conjunction of two independent events is equal to the likelihood of one event multiplied by the likelihood of the other event. Therefore, since the likelihood of rolling a 1 is 1/6 and the dice are independent, the likelihood of rolling two 1’s is 1/6*1/6=1/36. Here, we rely on probability theory to determine the likelihood of the conjunction of two events. The chance of rolling two 1’s is therefore 1 out of 36 possible outcomes.

Probability theories are used to develop predictive models, which are a set of equations that can be used to predict the results of measuring variables within the system being modeled. Physics uses predictive models to describe mechanical systems, which are systems composed of mechanical variables such as position and momentum. It’s important to keep in mind that the equations used in physics are not meant to describe what is ‘actually happening’ in the universe. Rather, they are tools we use to predict the results of measuring mechanical variables. For example, given the velocity and angle at which a projectile is launched, kinematic equations can be used to predict how far the object will travel before hitting the ground. These equations model projectile motion (a mechanical system) and predict the result of measuring distance (a mechanical variable). Quantum mechanics is a special area of physics where quantum theory is used to develop predictive models of mechanical systems.

Predictive models are employed in all disciplines that involve quantitative measurements. In cognitive science, which is the discipline that studies the mind and its processes, cognitive modeling develops predictive models of cognitive systems. For example, in a task where people have to choose between two alternatives, such as classifying an animal as a dog or a cat, models of decision-making are used to predict which alternative people will select and how long it will take them to make that decision. Similar to how quantum mechanics utilizes quantum theory to develop predictive models of mechanical systems, quantum cognition utilizes quantum theory to develop predictive models of cognitive systems.

Nevertheless, the question of “why bring quantum theory into cognition” remains. While there are several motivations, the one I will focus on here is how quantum theory incorporates the context of past events by allowing the system under study to be sensitive to observation. In reference to the example at the beginning of this post where the system is the pair of dice, suppose we roll one “quantum” die before the other. Quantum theory allows the likelihood of rolling a 1 with the second “quantum” die to change if we observe the result of rolling the first “quantum” die. Of course, a pair of dice are classical and not sensitive to observation, so the likelihood of rolling a 1 with the second die will not change. But, unlike dice, human behavior is contextual and sensitive to measurement.

One famous demonstration of how people’s judgements are contextual and can be affected by previous judgement is known as the Scandinavian problem (Tentori et al., 2004). In this experiment, people are first informed, “The Scandinavian peninsula is the European area with the greatest percentage of people with blond hair and blue eyes”. Then, they are asked to judge which of the following is more probable regarding an individual chosen at random from the Scandinavian population: (1) the individual has blond hair or (2) the individual has blue eyes and blond hair. Tentori et al. (2004) demonstrated that people will often regard (2) as more likely than (1). From a classical standpoint, this makes no sense. According to classical probability theory, the probability of the conjunction of two events is equal to the probability of one event multiplied by the probability of the other event. Since the probability of having blue eyes and the probability of having blond hair are both less than one, the probability of having blue eyes and blond hair must be less than the probability of having blonde hair. Clearly, human judgment is deviating from that expected by classical probability theory in the Scandinavian problem.

To make sense of this phenomenon, quantum theory treats judgment as a sequential process, where the first judgment sets the context for the second judgment. The option for the individual having blue eyes appears first, so the quantum model assumes that people first judge whether they think the individual has blue eyes. Suppose people decide that the individual has blue eyes. Now, when they judge whether the individual has blond hair, they are doing so from the perspective that the individual has blue eyes, in addition to being Scandinavian. Unlike classical probability theory, quantum theory allows the first judgment to alter people’s perspective such that people behave differently when making the second judgment. Due to the change in perspective, the likelihood of people judging that the individual has blonde hair increases so much that the likelihood that the individual has blue eyes and blond hair is greater than the likelihood of the individual having blond hair in isolation.

Note, the purpose of quantum cognition is not to explain why judging that the individual has blue eyes increases the likelihood of people judging that the individual has blond hair. Rather, the quantum model is designed to explain why the apparent logical fallacy occurs. That is, when making a judgment or decision, people’s reasoning can be altered by their previous judgments. The insights provided by quantum cognition shed light on our reasoning and help us understand how we make judgments in our everyday lives.

Prior to quantum cognition, the heuristic approach (Gigerenzer & Todd, 1999) was the predominant method for explaining human behavior that deviates from that expected by classical probability theory. Rather than predicting human behavior using a single set of axioms, the heuristic approach describes human behavior with different descriptive strategies for different situations. For example, the heuristic approach explains the Scandinavian problem using the representativeness heuristic, which states that people evaluate the probability of the different options based on how similar they are to a stereotype or a representative mental image. According to the representativeness heuristic, when people imagine a Scandinavian person, they imagine someone with blond hair and blue eyes, so they judge the randomly selected person to have both blond hair and blue eyes as being the most likely option, rather than just blond hair. The biggest weakness of the heuristic approach is that it lacks an overarching framework, and therefore does not offer strong, falsifiable predictions in novel settings. Quantum cognition offers an improvement over the heuristic approach because it is constrained using the axioms of quantum theory as an overarching framework that can formalize intuitions which have so far been “heuristically” explained, that is, according to specific circumstances of a single situation.

Want to test your knowledge of quantum cognition or provide feedback on the article? Please do so here.

References:

Gigerenzer, G., & Todd, P. M. (1999). Fast and frugal heuristics: The adaptive toolbox. In Simple heuristics that make us smart (pp. 3-34). Oxford University Press.

Tentori, K., Bonini, N., & Osherson, D. (2004). The conjunction fallacy: A misunderstanding about conjunction?. Cognitive Science, 28(3), 467-477.

Learn about Research in the Lab: Context effects in decision-making

Written by Gunnar Epping

Suppose you are looking for a new apartment and deciding between option A, which is expensive but in a great location, and option B, which is cheap but in a bad location. Also assume that given how you weigh price and location, you do not favor one option over the other such that there’s a 50% chance you select option A and a 50% chance you select option B.

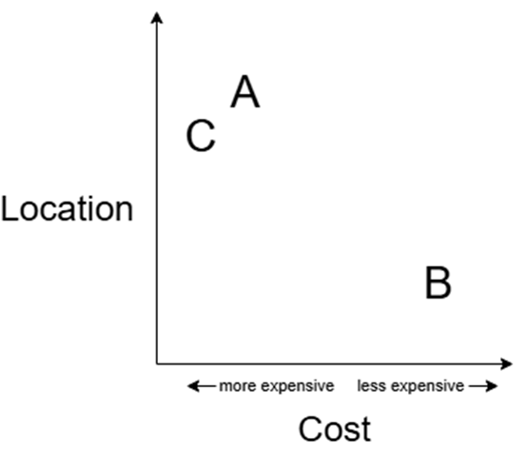

Now suppose, in addition to options A and B, you are also considering a third apartment, option C. Option C is slightly more expensive than option A and is in a slightly worse location than option A, but still a far better location than option B. The figure below illustrates the relative value of each option on the two attributes being considered.

Now that this third option has been introduced, how does this impact your decision-making process? Perhaps you may compare option A to option C and think to yourself, “Although both are more expensive than option B, option A is less expensive and in a better location compared to option C, so let’s go with that one.” This sort of thinking is an example of a context effect in decision-making. The context here is the set of options being considered. By changing the choice set from options A and B to options A, B, and C, option A looks like a better choice than option B. From a rational standpoint, introducing option C shouldn’t impact your indifference between options A and B because option C is irrelevant given that it is inferior to option A on both attributes. Nevertheless, decades of empirical research have reported evidence supporting the presence of context effects in decision-making (Huber et al., 1982).

Context effects are theorized to occur because of working memory constraints, attention, and the comparative process employed in decision-making. When only considering two options, you may be able to hold both options and their attributes in working memory when deciding between them. However, with the addition of more options, you may not be able to consider all options and attributes at once and instead attend to only a pair of options at one time. As a result, you make three comparisons when selecting your apartment (A versus B, A versus C, and B versus C) rather than simultaneously comparing A versus B versus C. When comparing A versus B, you are still indifferent between the two and don’t exhibit a preference for either option. When comparing A versus C, you develop a strong preference for option A since it is superior to option C on both attributes. When comparing B versus C, you develop a weak preference for option B. Aggregating your preference across the three comparisons, option A appears to be the best apartment.

Context effects that arise from changes to the choice set are not limited to consumer choice as they have also been found to impact perceptual decisions. For example, Trueblood et al. (2013) reported context effects when people evaluate the area of rectangles. The figure below depicts an example of a trial from this experiment, along with a plot depicting each rectangle’s relative height and width.

Although rectangles A and B both have the same area, people tended to judge rectangle A as having the greatest area among the three options.

Moreover, context effects are not limited to human behavior, as other animals have been shown to also exhibit context effects. For example, monkeys exhibit context effects using a similar perceptual task as described above (Parrish et al., 2013) and both honeybees and hummingbirds exhibit context effects in selecting flowers to forage from (Latty & Trueblood, 2020; Bateson et al., 2003). These studies support the idea that context effects are a universal property of choice behavior, regardless of setting or species.

People should be aware of context effects because it encourages us to reflect on the actual value or utility of different options, rather than being swayed by comparisons and irrelevant options. For example, businesses and marketers often exploit these effects to nudge people toward specific purchases. A company may offer 3 subscription plans that vary in terms of cost/month and number of months the subscription plan covers. They could attempt to manipulate you into purchasing a specific plan (call this plan A) by making one of the three plans inferior to plan A in terms of both cost per month and number of months. Therefore, developing an awareness of context effects helps people recognize when their preferences are being shaped, avoid being manipulated by marketing tactics, and make decisions that best align with their values and preferences. Want to test your knowledge of context effects in decision-making or provide feedback on the article? Please do so here.

References:

Bateson, M., Healy, S. D., & Hurly, T. A. (2003). Context–dependent foraging decisions in rufous hummingbirds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 270(1521), 1271-1276.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., & Puto, C. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: Violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. Journal of consumer research, 9(1), 90-98.

Latty, T., & Trueblood, J. S. (2020). How do insects choose flowers? A review of multi‐attribute flower choice and decoy effects in flower‐visiting insects. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89(12), 2750-2762.

Parrish, A. E., Evans, T. A., & Beran, M. J. (2015). Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) exhibit the decoy effect in a perceptual discrimination task. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 77, 1715-1725.Trueblood, J. S., Brown, S. D., Heathcote, A., & Busemeyer, J. R. (2013). Not just for consumers: Context effects are fundamental to decision making. Psychological science, 24(6), 901-908.

Welcome Hoyoung and Phillip!

Hoyoung Doh and Phillip Hegeman joined the lab as PhD students this Fall! Prior to joining IU, Hoyoung completed his B.A. and M.A. in psychology from Seoul National University, South Korea. Phillip earned B.S. degrees in mathematics and physics from the University of Missouri – Columbia in 2020, followed by a postbaccalaureate research fellowship at the National Institute on Minority Health & Health Disparities. Welcome!